During periods of low energy—such as intermittent fasting or exercise—immune cells step in to regulate blood sugar levels, acting as the “postman” in a previously unknown three-way conversation between the nervous, immune and hormonal systems. These findings open up new approaches for managing conditions like diabetes, obesity, and cancer.

Rethinking the Immune System

“For decades, immunology has been dominated by a focus on immunity and infection”, says Henrique Veiga-Fernandes, head of the Immunophysiology Lab at the Champalimaud Foundation. “But we’re starting to realise the immune system does a lot more than that”.

Glucose, a simple sugar, is the primary fuel for our brains and muscles. Maintaining stable blood sugar levels is crucial for our survival, especially during fasting or prolonged physical activity when energy demands are high and food intake is low.

Traditionally, blood sugar regulation has been attributed to the hormones insulin and glucagon, both produced by the pancreas. Insulin lowers blood glucose by promoting its uptake into cells, while glucagon raises it by signalling the liver to release glucose from stored sources.

Veiga-Fernandes and his team suspected there was more to the story. “For example”, he notes, “some immune cells regulate how the body absorbs fat from food, and we’ve recently shown that brain-immune interactions help control fat metabolism and obesity. This got us thinking—could the nervous and immune systems collaborate to regulate other key processes, like blood sugar levels?”.

A New Circuit Uncovered

To explore this idea, the researchers conducted experiments in mice. They used genetically engineered mice lacking specific immune cells to observe their effects on blood sugar levels.

They discovered that mice missing a type of immune cell called ILC2 couldn’t produce enough glucagon—the hormone that raises blood sugar—and their glucose levels dropped too low. “When we transplanted ILC2s into these deficient mice, their blood sugar returned to normal, confirming the role of these immune cells in stabilising glucose when energy is scarce”, explains Veiga-Fernandes.

Realising that the immune system could affect a hormone as vital as glucagon, the team knew they were onto something of major impact. But it left them asking: how exactly does this process work? The answer took them in a very unexpected direction.

“We thought this was all being regulated in the liver because that’s where glucagon exerts its function”, recalls Veiga-Fernandes. “But our data kept telling us that everything of importance was happening between the intestine and the pancreas…”.

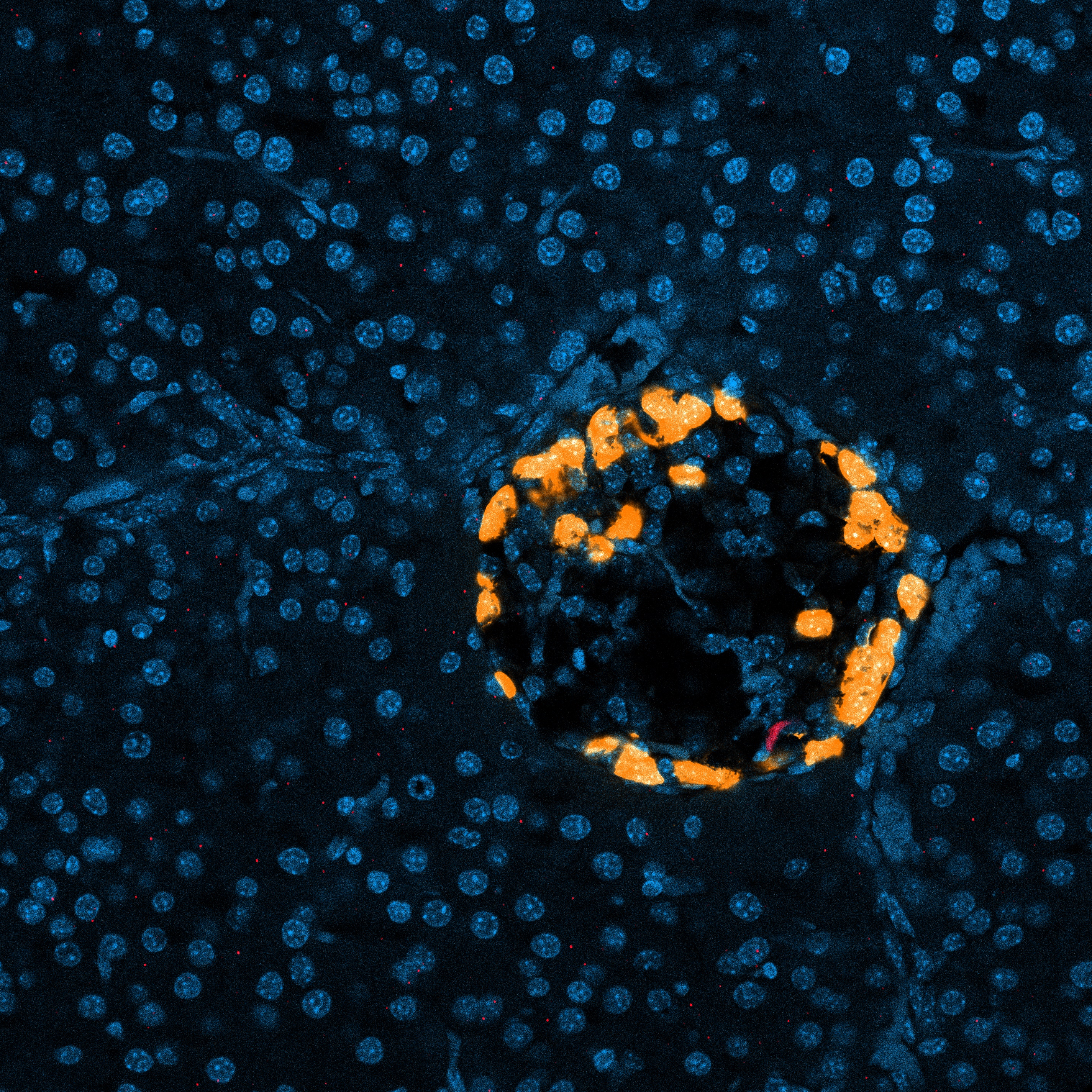

Using advanced cell-tagging methods, the team labelled ILC2 cells in the gut, giving them a glow-in-the-dark marker. After fasting, they found these cells had travelled to the pancreas. “One of the biggest surprises was finding that the immune system stimulates the production of the hormone glucagon by sending immune cells on a journey across different organs”.

Once in the pancreas, those immune cells release cytokines—tiny chemical messengers—that instruct pancreatic cells to produce the hormone glucagon. The increase in glucagon then signals the liver to release glucose. “When we blocked these cytokines, glucagon levels dropped, proving they are essential for maintaining blood sugar levels”.

“What’s remarkable here is that we’re seeing mass migration of immune cells between the intestine and pancreas, even in the absence of infection,” he adds. “This shows that immune cells aren’t just battle-hardened soldiers fighting off threats—they also act like emergency responders, stepping in to deliver critical energy supplies and maintain stability in times of need”.

It turns out this migration is orchestrated by the nervous system. During fasting, neurons in the gut connected to the brain release chemical signals that bind to immune cells, telling them to leave the intestine and go to a new “postcode” in the pancreas, within a few hours. The study showed that these nerve signals change the activity of immune cells, suppressing genes that anchor them in the intestine and enabling them to move to where they’re needed.

Implications for Fasting and Exercise

“This is the first evidence of a complex neuroimmune-hormonal circuit”, Veiga-Fernandes observes. “It shows how the nervous, immune, and hormonal systems work together to enable one of the body’s most essential processes—producing glucose when energy is scarce”.

“Mice share many fundamental biological systems with humans, suggesting this inter-organ dialogue also occurs in humans when fasting or exercising. By understanding the role of ILC2s and their regulation by the nervous system, we can better appreciate how these daily life activities support metabolic health. We’re eavesdropping on conversations between organs that we’ve never heard before”.

He adds that the immune system likely evolved as a safeguard during adversity, pointing out that our ancestors didn’t have the luxury of three meals a day and, if they were lucky, might have managed just one. This evolutionary pressure would have pressured our bodies to find ways to ensure that every cell gets the energy it needs.

“We’ve long known that the brain can directly signal the pancreas to release hormones quickly, but our work shows it can also indirectly boost glucagon production via immune cells, making the body better equipped to handle fasting and intense physical activity efficiently”.

Cancer, Diabetes and Beyond

The findings could open new doors for managing a range of conditions, notably for cancer research. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours and liver cancer can hijack the body’s metabolic processes, using glucagon to increase glucose production and fuel their growth. In advanced liver cancer, this process can lead to cancer-related cachexia, a condition marked by severe weight and muscle loss. Understanding these mechanisms could help develop better treatments.

“Balancing blood sugar is also critical, not only for preventing obesity, but also for addressing the global diabetes epidemic, which affects hundreds of millions of people”, remarks Veiga-Fernandes. “Targeting these neuro-immune pathways could offer a new approach to prevention and treatment”.

“This study reveals a level of communication between body systems that we’re only beginning to grasp”, he concludes. “We want to understand how this inter-organ communication works—or doesn’t—in people with cancer, chronic inflammation, high stress, or obesity. Ultimately, we aim to harness these results to improve therapies for hormonal and metabolic disorders”.

Original paper here.

Image caption: During fasting or exercise, immune cells (red) migrate to the pancreas and stimulate glucagon-producing cells (orange) to regulate blood sugar, with cell nuclei shown in blue.

Text by Hedi Young, Science Writer and Content Developer of the Champalimaud Foundation's Communication, Events & Outreach Team.