Developed by an international consortium of 117 experts in legal, ethical, clinical, and AI domains—and featuring Champalimaud Foundation (CF) Principal Investigator Nikolas Papanikolaou—the framework provides a detailed roadmap for creating trustworthy medical AI, from the earliest design stages all the way through clinical deployment and monitoring.

A Global Collaboration

“Our goal is to connect every stage of an AI’s lifecycle—design, development, validation, and deployment—so no one is left in the dark about how these tools work, or how to keep them safe and fair”, says Nikolas Papanikolaou, who leads CF’s Computational Clinical Imaging Lab and helped spearhead the FUTURE-AI initiative.

Originally focused on Europe, the group soon grew to include specialists from 50 countries across North America, Asia, Africa, and the Gulf region. “We wanted legal scholars, ethicists, healthcare professionals, and computer scientists all at the same table”, says Papanikolaou. “AI for medicine is never just about coding—there are social and ethical considerations, regulatory factors, equipment differences, and more. FUTURE-AI merges all these fields into one blueprint”.

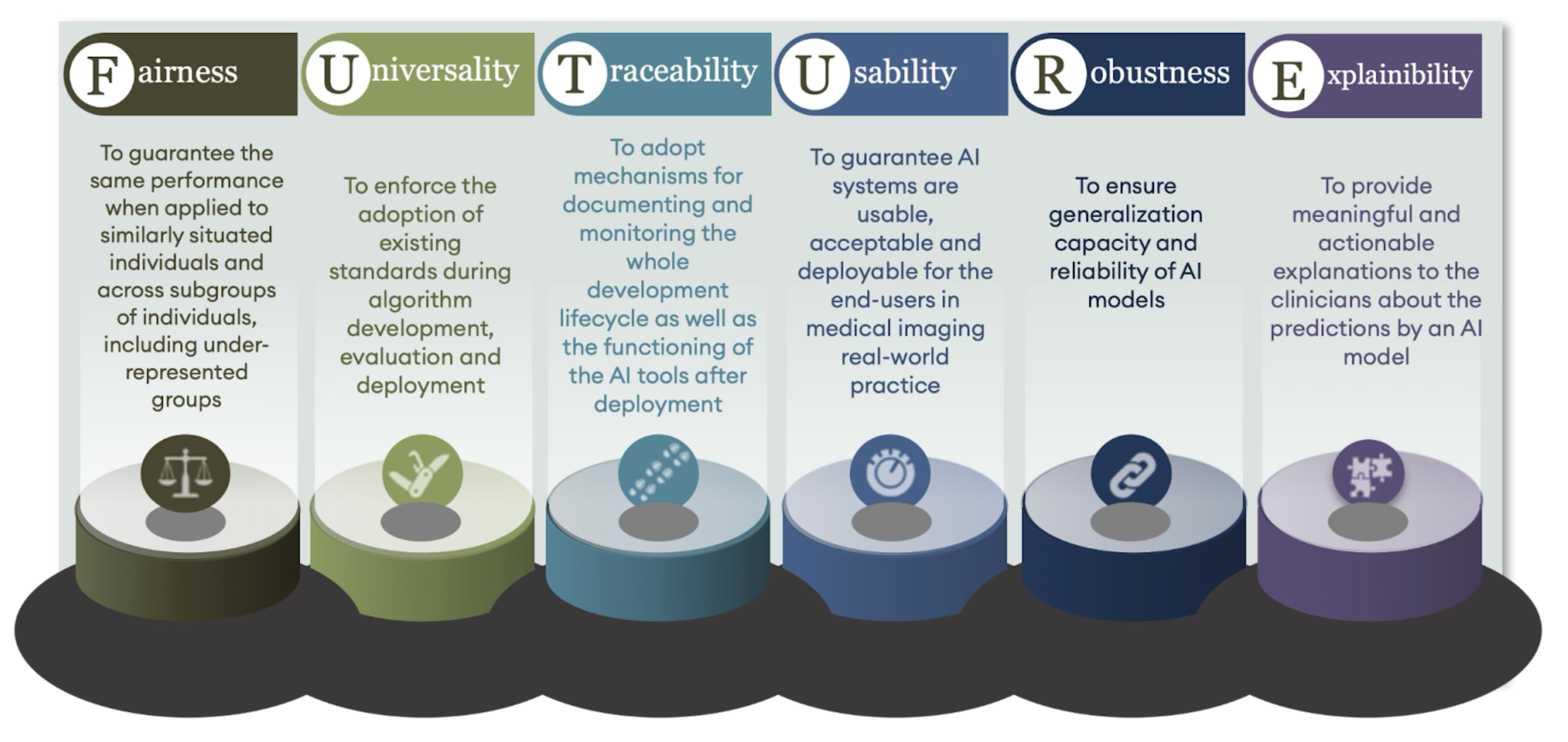

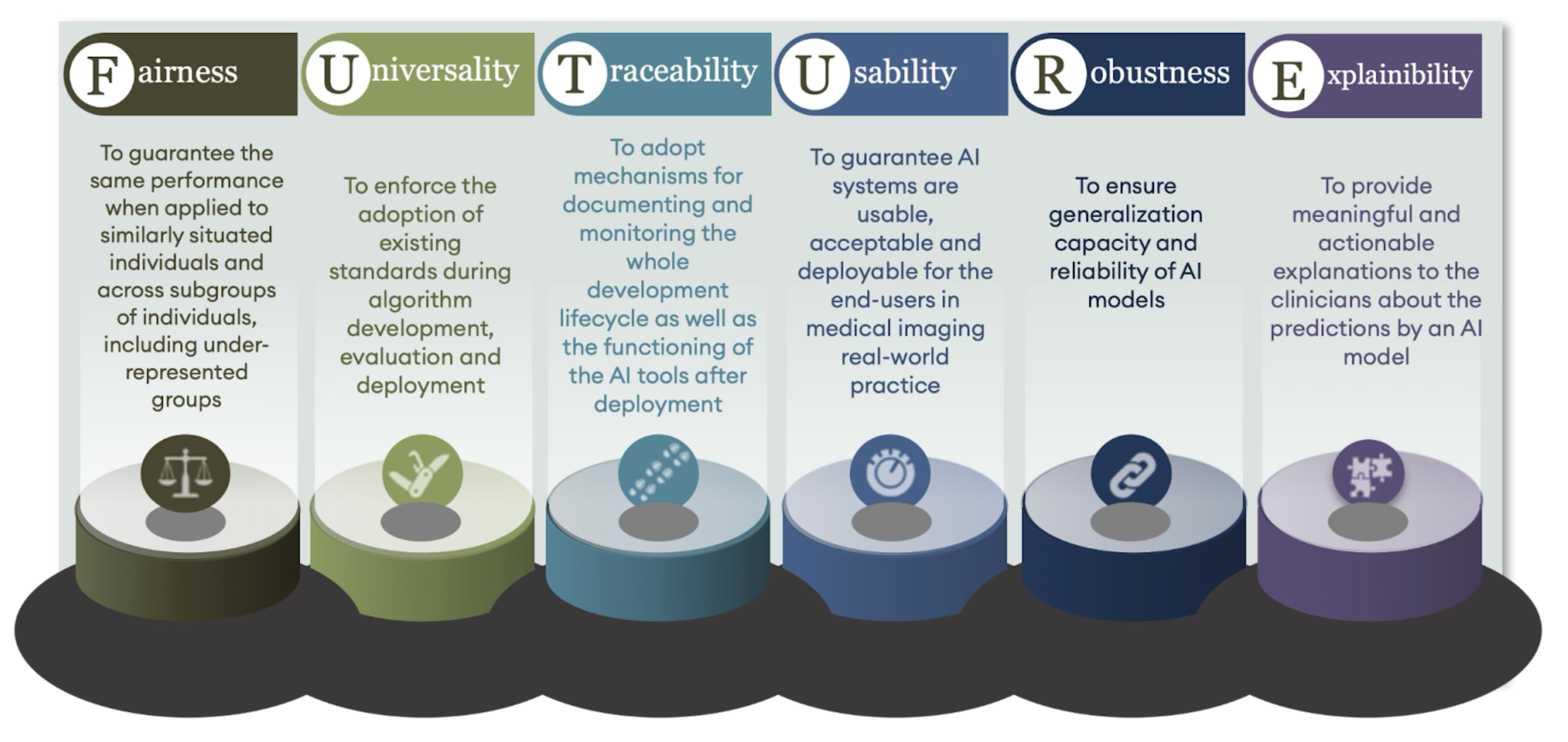

After two years of intensive collaboration, the consortium created 30 recommendations, organised under six guiding “pillars”: Fairness, Universality, Traceability, Usability, Robustness, and Explainability— forming the mnemonic FUTURE. For example, fairness is about AI working well for all patient groups, reducing biases that can harm underrepresented populations, while Explainability is about clinicians needing to understand, at least at a high level, why an AI system arrives at its conclusions.

Papanikolaou, who played a key role in shaping the Usability guidelines, underscores how high the stakes are: “We don’t have the luxury of making mistakes when it comes to patient health. FUTURE-AI is ultimately about patient safety and preventing risky shortcuts in AI development”.

The Value of Diverse, Multicentre Data

While many AI guidelines focus on a single stage—like model-building or data ethics—FUTURE-AI looks at four main phases that span the entire lifecycle of a healthcare algorithm.

The Design phase brings all stakeholders on board early—clinicians, data scientists, hospital administrators, and ethicists. “If you don’t involve everyone from day one, you risk developing a system that sits on the shelf unused”, stresses Papanikolaou.

In the Development phase, FUTURE-AI tackles the risk of “overfitting”, which happens when algorithms are trained on narrow datasets. Instead, developers should collect large, diverse, and high-quality datasets—what Papanikolaou calls the three key ingredients: “Quantity, Quality, Diversity”.

He recalls how his team’s earlier cancer-detection models trained on small, local datasets achieved 90% accuracy—only to fall to 60% when tested at a new hospital. This improved dramatically in projects like ProCAncer-I, which pooled data from more than 13,000 patients at 13 institutions. “All of a sudden, the same algorithms performed much better in new contexts”.

The third phase, Validation, involves rigorous checks on external data—examining how well the model performs with different equipment and patient populations. Finally, in the Deployment phase, the framework urges ongoing monitoring: “Healthcare data and hardware constantly change. An MRI machine might get a software update that affects image contrast, which can weaken an AI tool’s performance over time”.

Next Steps: MLOps and Real-World Impact

A recurring theme in FUTURE-AI is the need for continuous oversight and multidisciplinary teamwork. “We’ve seen computer scientists develop impressive systems in isolation”, Papanikolaou explains. “But if they don’t involve frontline clinicians or data managers, they might overlook an obvious pitfall—like the fact that an image annotation was done differently at another hospital”.

Papanikolaou’s team is developing “MLOps,” a specialised software infrastructure for medical imaging AI. It’s designed to prevent AI model degradation by continually monitoring its accuracy and reliability. “With MLOps, we plan to deploy our radiology models in a way that’s scalable and auditable”, Papanikolaou says. “Data scientists can retrain an algorithm as new patient data come in, while clinicians can easily see how the tool performs. When there’s a software update in an MRI machine, we’ll be notified, so we can re-validate the model”.

Real-world examples show how transformative this can be. Papanikolaou points to advanced models developed by his team that have already cut down on unnecessary biopsies by correctly identifying a subset of patients who do not have cancer—potentially sparing over 20% of them from an invasive procedure. “That’s a prime example”, he notes. “But to keep those gains, we must watch our models very closely”.

“We can’t just build an algorithm in a silo and assume it’s perfect”, Papanikolaou says. “If people don’t trust it, if it’s biased or breaks down with new data, it will be completely worthless. But if we do it right—by following guidelines like FUTURE-AI—we can genuinely improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden on healthcare systems. That’s the real promise of AI in medicine”.

Image: FUTURE-AI developed 30 recommendations, structured around six key pillars: Fairness, Universality, Traceability, Usability, Robustness, and Explainability—together forming the mnemonic FUTURE.

Text by Hedi Young, Science Writer and Content Developer of the Champalimaud Foundation's Communication, Events & Outreach team.