- Clinical Programmes

Immuno-oncology Programme

A prime example of cancer treatment personalisation

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) designated Cancer Immunotherapy as the most relevant scientific and therapeutic breakthrough of the past two years (2016 and 2017). This area of Oncology has certainly known major progress in knowledge, from underlying mechanisms to the role of the immune system in tumour development. It has thus been possible to develop new drugs and innovative strategies in cancer treatment where the patient’s own immune system plays the main role in the fight against the disease.

At the CCC, the increasing use of immunotherapy in the treatment of patients with advanced forms of oncological disease has become a reality through scientific development and the approval of innovative drugs by the international organisations that regulate the introduction of new pharmaceuticals (FDA and EMA).

A clinical research programme in immuno-oncology was launched in 2017. Its goal is to study and develop innovative immunotherapy modalities, especially in the field of cellular immunotherapy.

This programme works under the leadership of Professor Markus Maeurer, a leading scientist and immunology specialist, and is based on a close collaboration with Professor Elke Jaeger, Director of the Oncology and Haematology Service at the Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, and with Professor Steven Rosenberg, who heads the Immunotherapy Department at the National Institutes of Health, in Washington, USA.

Immuno-oncology Programme

Immunotherapy

Fighting cancer from the inside

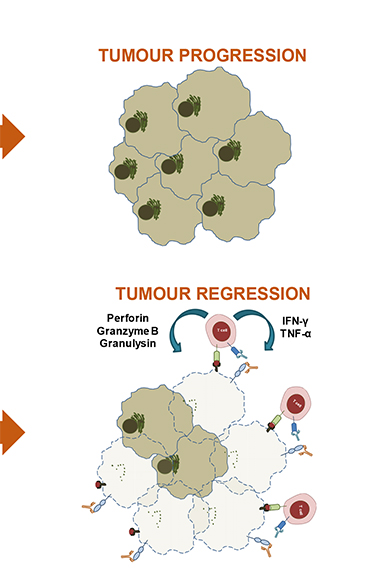

Our immune system is equipped and prepared to fight against cancer. Most people are protected by specialised cells of the cellular immune system, especially effective at detecting and destroying tumours. However, in some individuals, cancer cells “discover” how to escape the immune system and become able to avoid immune recognition – and sometimes even to protect themselves from immune attack. The goal of immunotherapy is to alter this situation, so as to enable the immune system to fight cancer cells and keep them under control for a long time.

There are currently five different classes of immunotherapy: anti-cancer vaccines (vaccination against proteins that are exclusively expressed by cancerous cells), immunomodulators (that activate the immune system and end the paralysis imposed by cancer cells on immune cells), targeted antibody therapies (antibodies that attack cancer cells), oncolytic viruses (modified viruses that infect and kill cancer cells, and alert and activate the immune system to better fight cancer), and lastly, cellular immunotherapy. There are also several ways to use the patient’s own immune cells to combat cancer. At the Champalimaud Foundation, a clinical and research structure is in place to provide cellular therapeutic options to cancer patients. For instance, a patient’s immune cells can recognise the tumoral cells of that same patient. Those immune cells can be found directly in the tumoral tissue or around the lesion. Sometimes, those immune cells are also found circulating in the blood at very low levels. They tried to fight the cancer cells but lost the battle.

At the Champalimaud Foundation, we are now trying to learn in detail the molecular composition of each individual cancer. There are many similarities between cancer typologies, but also many differences, and each patient seems to have his or her own individual mutations present in their tumoral tissue, apart from the molecular changes typically associated with cancer. We use various methods to exactly determine all the mutations that occur in cancerous lesions, as well as the different proteins that express themselves at a given time. In this way, not only can we collect detailed information about the cancer, but also map the immune response in great detail by using advanced methods against cancer cells.

Immune cells are then extracted from the patient’s blood or from his or her tumour and expanded using a “intelligent” mix of immune system “growth hormones”, with the sole aim of cultivating those immune cells that are particularly good at recognising tumoral cells while at the same time ensuring the memorisation of the response by the organism for the long run.

By doing this, we go from a situation in which there are few immune cells capable of attacking the cancer to one where there are billions of cells that can potentially be used in therapy. Typically the patient’s non-functional immune cells are removed and replaced by functionally active immune cells specifically directed against the cancer cells. Very often these immune cells can be further activated once inside the patient, to make them fight even better and prepare them to afford better protection in the future.

In the last ten years, the field of immunotherapy has greatly evolved and innovative technologies have been developed to better define cancer’s molecular targets. Furthermore, new discoveries have helped to “adapt” the immune response to each patient. This approach can also be called “precision medicine”: we need to better identify cancer cells, as well as potentially protective immune responses, to develop and eventually offer innovative, personalised therapies to cancer patients. This approach is not a “one-stop, one-shop” solution; it is grounded in a multidisciplinary concept of clinical practice and clinically relevant biological research.

At the Champalimaud Foundation, we call these efforts Immuno-surgery: the immune response must be as precise as a surgical scalpel and must not harm the patient. The aim is to launch a multidisciplinary attack on cancer. Afterwards, the patients must be regularly monitored, for a long time, to detect premature relapses, understand the molecular and immune causes of the relapses, and develop new prevention and treatment strategies.

This can only be done by establishing strong collaborative networks within the institutions themselves and with other institutions that pursue the same goal and have the same vision. Only with strong partners who actively participate in the advance of science and in clinical progress will we be able to prepare for the “fusion” of clinical and pre-clinical applications in immunotherapy. We hope to achieve this fusion in medicine – between partner institutions, between individuals who promote innovation and technological development, between scientists, doctors, and the most important partner of them all: our patient.

Projects: