“I’m exactly as I was 10 years ago”, says Kina García, a Spanish woman from the Granada region, as she addresses by Zoom, from her home, the audience of the International Conference on Neurodegenerative Diseases, gathered on a Saturday morning at the Champalimaud Foundation’s auditorium, in Lisbon. The date is appropriate: it is September 21 – World Alzheimer's Day.

Kina García is referring to her cognitive state: ten years ago, at the age of 59, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She was then enrolled into a clinical trial of aducanumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets deposits of the protein amyloid beta in the brain, which appear early in the course of the disease, before the onset of early symptoms of cognitive decline.

She was lucky, she tells the audience. She was given the maximum dose of the drug from the start (she didn’t know this then, the trial being randomised and blind), and the drug had a significant effect on her, contrary to what happens in many other cases. “It was effective for me”, she says.

In general, the results obtained with this and other available immunotherapies against AD, which were once considered very promising, have been disappointing. Accordingly, during the two days preceding García’s participation, leading experts in neuroscience had been intensely discussing the latest advances in the early detection and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases – mainly of AD, but also of Parkinson’s Disease (PD).

The conference was organised by the Champalimaud Foundation, the Fundación CIEN (Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Neurológicas), based in Madrid, and the Fundación Reina Sofía – and counted with the presence of Queen Sofia, mother of the King of Spain and executive president of the Foundation that bears her name.

The international participants at the conference presented new, more recent views of AD, as well as alternative, non-pharmacological, tools to diagnose and fight this disease, which robs its victims of everything that once made them themselves. At later stages, patients stop recognising their loved ones and become severely dependent.

Although the conference targeted neurodegenerative diseases in general, Alzheimer’s was naturally at the center of the debates, not only because it is most common form of neurodegenerative disease causing dementia in older populations (around 50% of cases in Portugal), but also because it is currently the most studied and well-known of this type of pathologies.

“These are the most exciting times”, said Pascual Sánchez-Juan, from CIEN, in his talk. “We now know more about the mechanisms of disease and we know their progression is not a linear process. And we have to be more pragmatic.”

One of the reasons accounting for the difficulty in treating AD, invoked by many speakers, are the high rates of co-pathologies that come with it. “Only a minority of cases are pure AD”, said Sandra Tomé, from Leuven Catholic University. Various brain pathologies are actually frequently present together in AD-related dementia.

The best-known hallmarks of AD are the formation of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (whose main ingredients are, respectively, the proteins amyloid beta and tau). But there can also be vascular degeneration, and in 50% of the cases, deposits containing a protein called TDP-43, more recently identified, which is thought to mediate neurodegeneration, . “The worst cognitive decline and brain mass loss happen when TDP-43 pathologies are present”, said Tomé.

Gabor Kovacs, from the University of Toronto, a top researcher in the field, “looked beyond the brain” at non-cerebral factors such as diet, pollution, liver disease, concluding that “patients with similar symptoms can have very different combinations of brain pathologies”.

Diego Sepúlveda, from the University of Hamburg, pointed out that this diversity was even present in a large study of familial early-onset AD in Colombia, inspite of the fact that all family members carried the same AD-causing mutation and led similar lives. The patients’ presented a “surprising heterogeneity”, with no two patients having the same age of onset, disease duration, etc..

This contributes to explain why there has been no single treatment that works against Alzheimer, and no single circulating biomarker (in the spinal fluid or the blood) to diagnose the disease’s status and progression to dementia. “It would be like asking for a pill to make you a good tennis player”, noted one of the participants. “AD is a multifactorial brain disease.” Realizing that each AD case is a case on its own may help to deal with AD.

It is also a disease intricately linked to ageing. Will it be possible to stop ageing? Some experts believe it will, others do not agree. Whatever the future holds, a pill against ageing will not be coming anytime soon and, in the meantime, less universal, more personalised alternatives must be found.

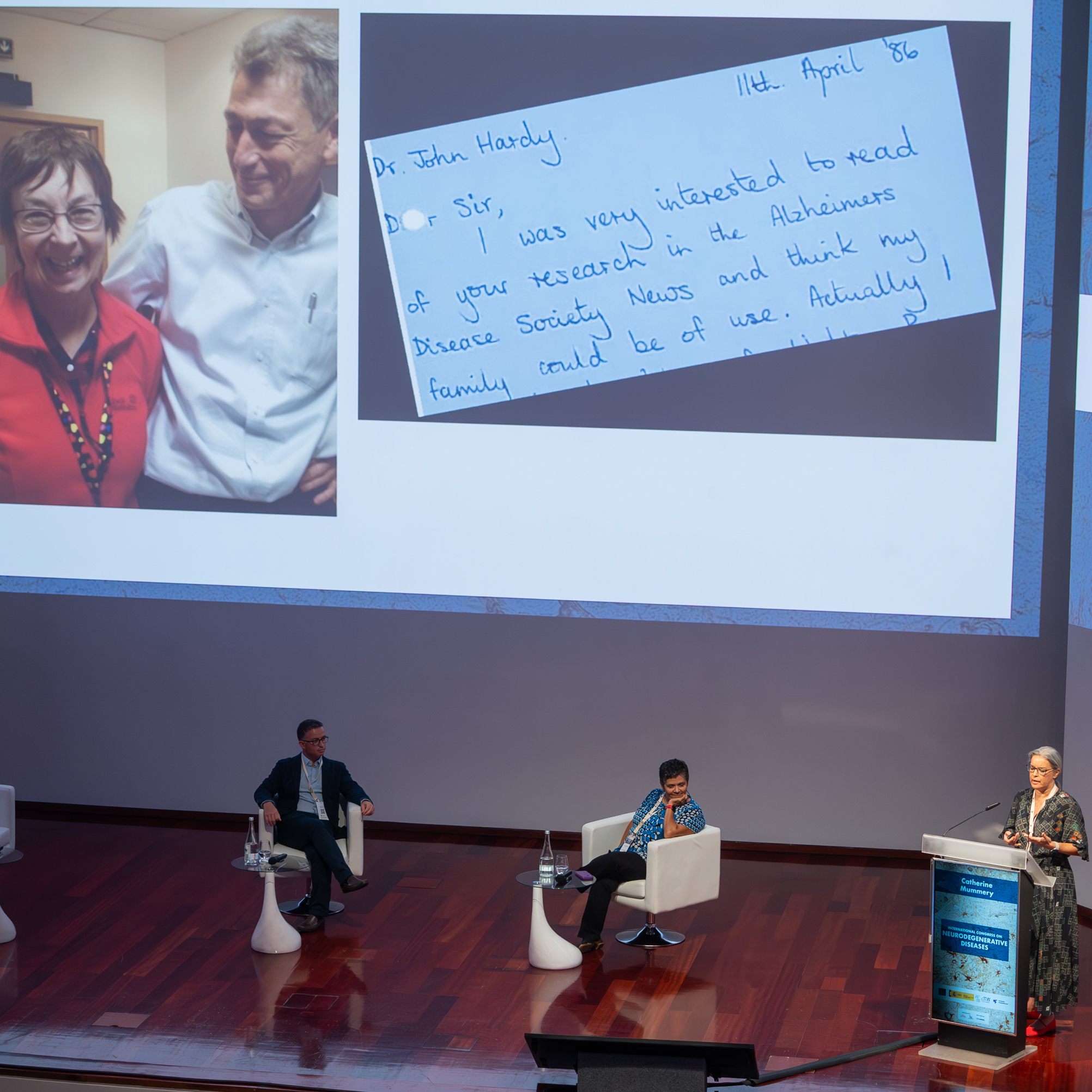

Apart from anti-amyloid beta therapies, which although dramatically removing this protein from the brain, have had very modest results on clinical symptoms of cognitive decline, tau suppression therapies have also begun to be the object of research. In particular, genetic therapies “to reduce tau levels at creation”, as Catherine Mummery, from University College London, explained. Tau pathology is the one that best correlates with cognitive decline and the clinical onset of AD and it is thought that tau mediates amyloid beta toxicity.

The activation of the microglia (the primary immune cells of the central nervous system) by the presence of amyloid beta plaques is also being looked into, as well as the role of low-grade inflammation in the brain. These could also become targets against AD-related dementia.

Given that AD is a disease of ageing, what do we know about the biological age of patients? It has become clearer, in recent years, that biological age can differ from chronological age and is associated, in particular, with lifestyle habits and the environment (https://fchampalimaud.org/news/check-up-26-why-are-younger-people-incre…). “Biological age is variable and can be modified, and it can also be measured” by so-called biological clocks, based on sets of proteins, said Alfredo Ramírez, from the University of Cologne. Could there be a deviation from chronological age in AD patients? In other words, could these patients be ageing faster, and could there be away to slow the process down?

The talk given by Henne Holstege, from Amsterdam University Medical Center, was, in a way, a speculation on these issues. She presented results from a study on the brains of nearly 500 cognitively healthy, non-demented centenarians who had donated their brains for this study. And when she looked at their brains, she exclaimed, “they looked 80-ish!”. No amyloid beta plaques, no vascular degeneration… “How was it possible?, she asked. “Are centenarians genetically protected against AD?”

More generally, we can ask whether we will one day be able to “trick” ageing as these centenarias appear to do. This is not unheard of in Nature: animals such as the axolotl, a Mexican salamander, live exceptionally long without showing the typical signs of biological ageing.

Non-pharmacological interventions were also considered by several speakers for the treatment of AD, such as brain stimulation, namely transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, which has become better known, in the past few years, as a treatment against drug-resistant depression.

Other such interventions, mainly for Parkinson’s Disease, were also discussed. “Non-pharmacological interventions are going to increase because they are holistic – exercise, for instance”, said John Krakauer, from the Champalimaud Foundation, who chaired the session on “digital therapies”.

“Interventions have to be ‘dirty’, complex, measurements have to be holistic”, he added, “and we have to combine them with more targeted pharmacological interventions.”

Daniela Pimenta Silva, from the University of Lisbon, talked about the benefits of training PD patients on virtual reality treadmills, in order to reduce the risk of falls in those at risk. She further mentioned a trial of an immersive game, MindPod Dolphin, in which patients have to control a swimming dolphin with their own body movements, as a possible intervention for improving motor control in these patients.

On the subject of assessing the effect of PD medication,

Dina Katabi, who spoke online via Zoom from her lab in MIT, proposed an approach that involved gait. “Gait decline is a robust biomarker of disease progression”, she explained. And so it would be possible, using a device with artificial intelligence (AI), to remotely track patients’ response to medication through changes in their gait speed.

On the other hand, nocturnal breathing could serve to detect PD and to predict its severity, she added. REM sleep, the part of the sleep cycle during which we dream, could also be used as a digital biomarker for PD. Katabi then asked a million-dollar question: will AI one day allow us detect PD before clinical diagnosis?

To wrap up the conference, on World Alzheimer’s Day the floor was given not only to Kina García, who lives with AD, but also to patient associations for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's from Portugal, Spain and Europe – along with neurologists, geneticists, and other researchers – to discuss the main challenges and difficulties they face.

Maria do Rosário Zincke, from Alzheimer’s Europe and Associação Alzheimer Portugal, stressed the importance of patients being more involved in research projects at every stage. Patients can “ask questions that may not have been considered by researchers”, she said.

The importance of brain biobanks for research purposes was also pointed out, and Marcelo Mendonça, from the Champalimaud Foundation – one of the organisers of the conference and chair of the session – asked for ideas about how to involve patients in basic research on animal models.

Isabel Santana, from the Medical School of the University of Coimbra, had a ready reply: “In cancer, it works very well. It’s a great example; we should follow it.”

Text by Ana Gerschenfeld, Health & Science Writer of the Champalimaud Foundation.